Introduction

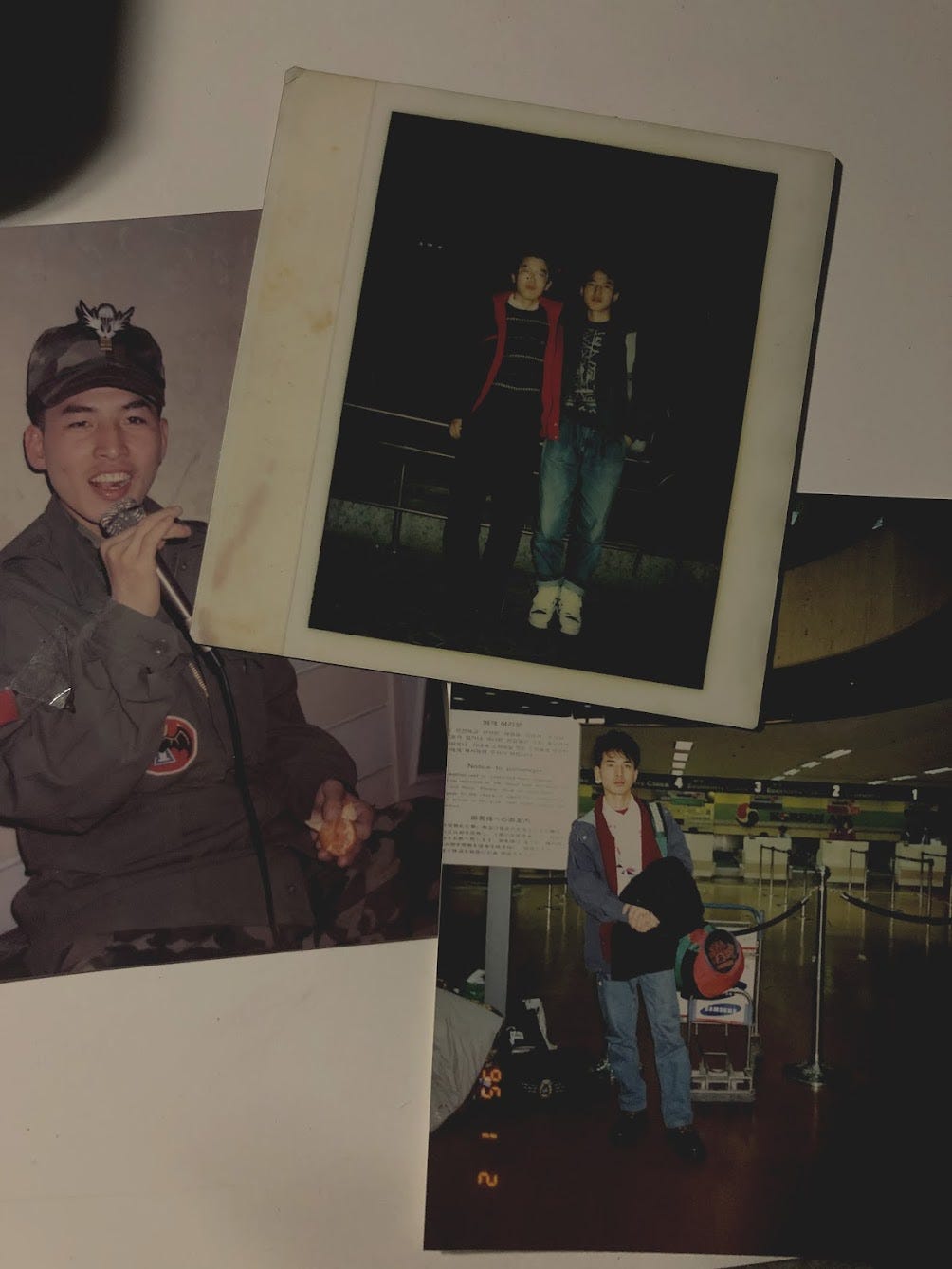

In my personal experience, growing up as an only child was to grow up privileged. Having to support only one child, my parents weren’t ever hesitant to send me on school camps and ski trips. Even now, they are paying for my international tuition fees and doing everything in their power to support my aspirations. I’ve never had to compete with someone else for their attention or worry about living a life of hand-me-downs.

My parents are unconventional in many ways, particularly as Asian parents. School was never a measure of my worth or potential, and they prioritised authenticity over maintaining ‘face’. Whenever I achieved anything they were the first to congratulate me, but also the first to humble me. This, I have always been especially grateful for. All that matters to them is that I’m kind and happy.

Of course, no parent is perfect and despite these privileges, I have my share of repressed resentments towards them, but considering the unconditional love I have received and continue to receive from them, it’s incomparable

Moving Out

I’m eighteen now, and there are less than three months left till I leave the comfort of my own home. By September, I’ll be on the other side of the world, chasing my dreams of academia and writing. Since obtaining my letter of acceptance, I have spent my nights contemplating how I will navigate the barriers of distance and time between myself and my parents. Inside the frenzied whirlpool of worries are questions such as: Do I know my parents enough to maintain our close bonds without proximity? Who even were they before me? Will they become the people from before once I leave? Wait, do I know my parents at all?

The prospect of knowing your parents is a strange one. You assume you know them because they’ve been in every part of your life. That is until you remember that although you don’t have a life before your parents, they have a life before you.

Thus began my frantic chronicling.

I created four documents:

Mum’s Life Before Me

Dad’s Life Before Me

Mum’s Life After Me

Dad’s Life After Me

I wrote down any anecdotes of their past they’d told me, memorable conversations we’ve shared, and the various things I’ve noticed about them throughout my eighteen years of life.

Then I began to create a list of questions:

What are some of your best memories as a child? Do you miss your childhood, and if you could keep one thing from that time, what would it be?

When did you realise you wanted to leave Korea? Was it an exact moment or something that built up over time? In what ways did you change by leaving?

What was your first experience of love like? How did you grow after that experience, what did you learn? What made you realise it was love?

When I presented my mum these questions she was completely unfazed. Apparently, she had this same exact crisis just last year on our trip to Korea so she understood my paranoia completely. I have yet to properly record the answers to my question bank, but the simple act of devising my inquiries softened the blows of uncertainty. There was step by step solution to the mysteries of their past.

However, there was a larger issue at hand.

I love being an only child. I like who I am because of it and I’ve never longed for a different life. Yet there is this one thing, this singular thing, that I must face at the expense of solitude: the obligation of memory.

Here’s a series of texts I sent my friend at three in the morning, when he asked me why I was suddenly worried about the death of my parents:

Growing up also means confronting the mortality of your parents.

Three years ago, my childhood best friend passed away from cancer. The worst part of losing someone you love is the ways your memory fails you. As months passed, the sound of her voice, the specific layout of her face, and even fragments of her personality started fading away. It wasn’t until I spoke to her younger sister, that I realised things would be okay. There was someone else in this world who was burdened with the obligation of remembering. I wasn’t alone.

But in the case of my parents, they are to me what they are to nobody else. They have decades left to live yet it feels as though I’m murdering their spirits each time I forget something about them. There is no resolution to this self-imposed responsibility of mine, at least not now, only acceptance. The best I can do is love them, and remember why I love them because as long as my love for them persists, they remain with me.

Moving On

Let this be a reminder to ask your parents more questions. Let them talk about themselves for once even if it bores you to death. And of course, remember to tell them you love them, not as a souvenir to your goodnights and goodbyes, but all on its own. I love you because I love you.

I don’t really know what I was trying to say by writing this piece. Maybe I’m leaving marks of myself for whoever is burdened with the obligation of remembering me. Or maybe I’m just trying to make adulthood seem less scary by writing it down, reducing it to mere sentences on the screen that can be deleted.

this. as a fellow korean-aus girl but also as a child of my parents- this post is so yes.